Carol Pope

Growing food where deer roam

Carol Pope

It’s a big challenge growing food where deer roam daily, grazing and razing every palatable morsel to the ground. Carol Pope suggests edibles to grow.

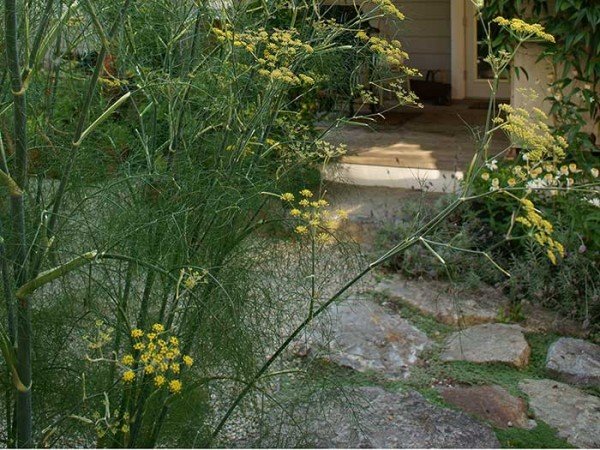

How to enjoy edible seeds from your garden

Carol Pope

In winter, enjoy tasty, healthy, organic edible seeds from three prolific plants — bronze fennel, cilantro and lovage. Carol Pope explains how.

Microgreens give taste of summer all winter

Carol Pope

In winter, you can enjoy fresh herbs like basil and crisp, fresh salad greens by growing microgreens indoors. Here's how.

Physalis alkekengi: 4 facts about this decorative fall plant

Carol Pope

To get into the Halloween spirit, pick up a decorative pot of Physalis alkekengi, a.k.a. liv’n lantern, Chinese lantern plant, strawberry ground cherry...