Since childhood, I’ve been convinced that there’s no better way to spend a rainy afternoon than to search through the shelves of an out-of-the-way second-hand bookstore. Although these establishments have become increasingly rare over the years, they are far from extinct, and are further enhanced by several good websites that specialize in second-hand books.

It was in this way that I first became acquainted with the writing of the two Strickland sisters. Born in England at the turn of the 19th century, they immigrated to Canada with their Scottish Orkney Islands husbands to become settler-homesteaders in Upper Canada (now Ontario) in the early 1830s. You may know them better as Catharine Parr Traill (1802-99), who wrote The Backwoods of Canada (1836) and The Canadian Settler’s Guide (1854), and Susanna Moodie (1803-85), justly celebrated for her Roughing it in the Bush (1852).

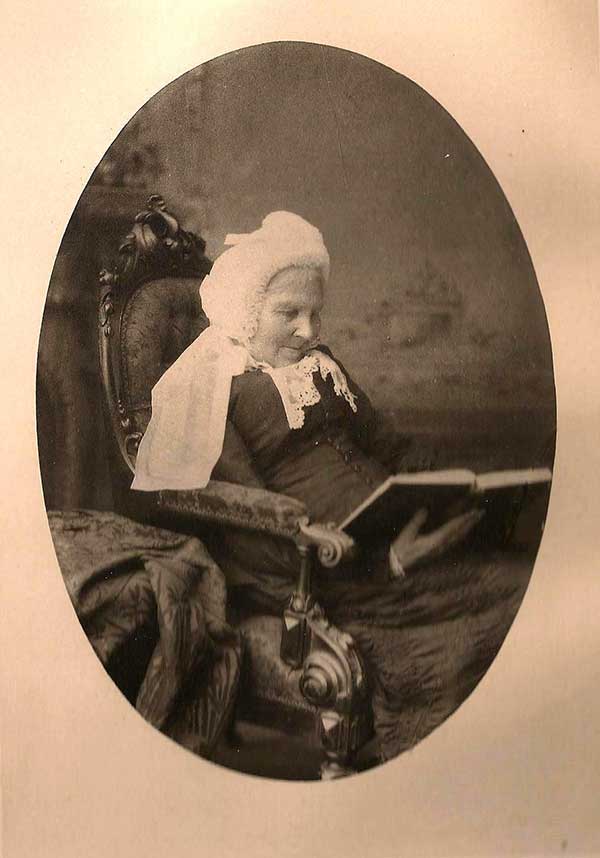

Born just 23 months apart, the two sisters shared much in common, but it was Catharine who proved to have the keener eye when it came to describing and documenting the landscape and plants of her adopted homeland. One of the most widely read Canadian authors in the 1860s, Catharine had long maintained a collection of dried plant specimens — which she called her Hortus siccus (i.e., “herbarium”) — together with copious notes about all of the native flowers, shrubs and trees that she encountered in Ontario. Some were familiar, but most were not.

After 27 years of unrelenting labour in the backwoods, her husband, Lieutenant Thomas Traill, died in 1859 leaving Catharine the sole provider for herself and her seven surviving children. She quickly set about organizing her botanical notes into book form, and in 1861 (having received encouragement from several professors at the University of Toronto) Catharine began to shop her manuscript around to various Toronto publishers. But in a city with a population of only 45,000, all the firms she contacted felt that the book was too long and the subject too specialized to be profitable.

In order to improve her chances of getting published, Catharine asked her niece (Susanna Moodie’s second daughter) Agnes Dunbar FitzGibbon (1833-1913) to supply illustrations for the book. At the time, Agnes FitzGibbon was the busy wife of a Toronto barrister, but when her husband Charles FitzGibbon died in February 1865, 32-year-old Agnes agreed to help her aunt, as she now found herself in similar circumstances: A widow with six children to support.

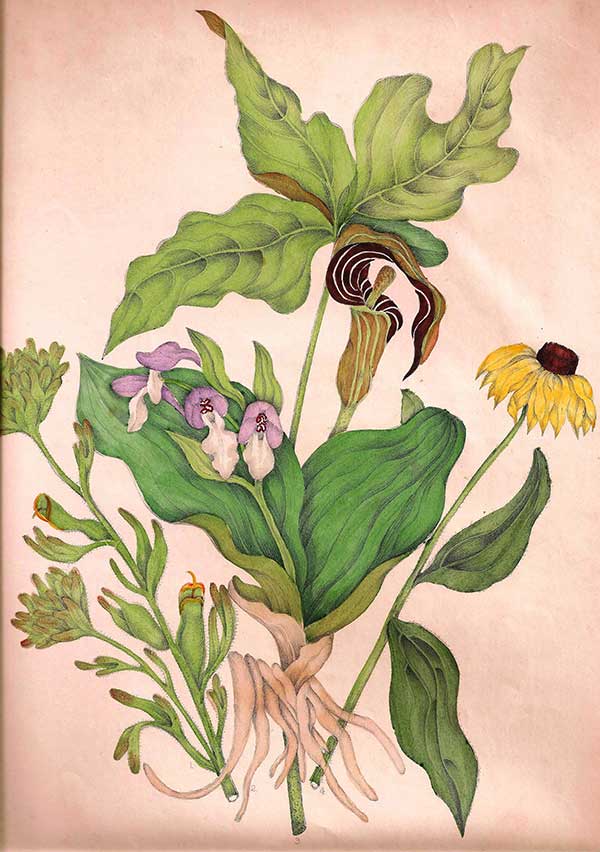

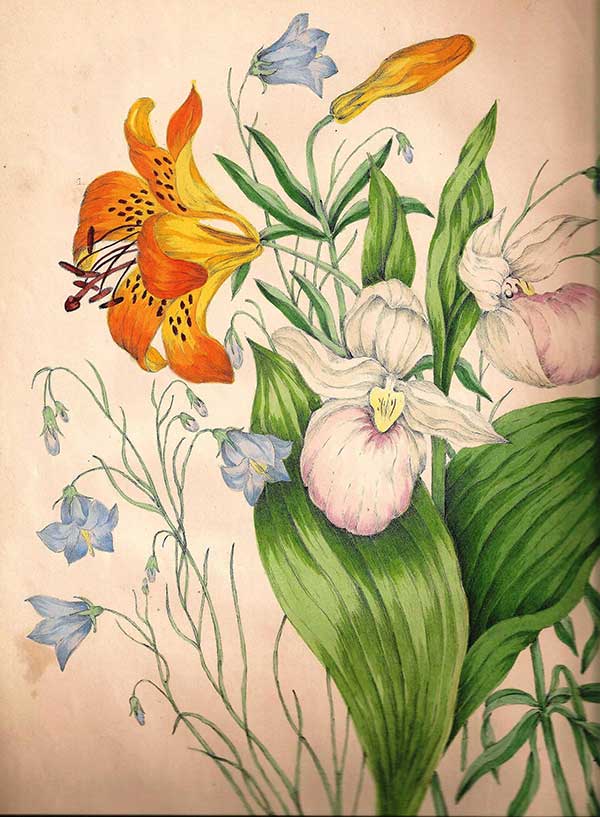

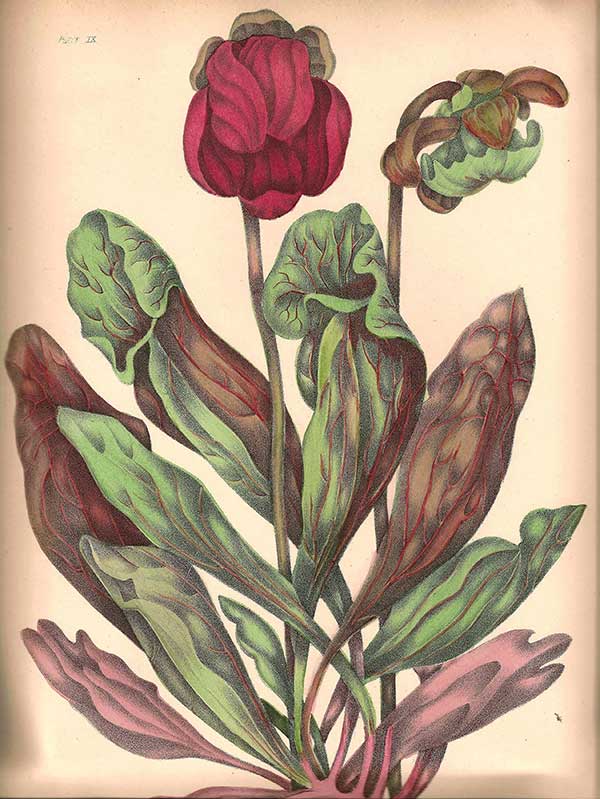

In November 1866, a Montreal firm agreed to publish Canadian Wild Flowers with the proviso that Catharine and Agnes would personally supply the illustrations in addition to signing up 500 subscribers, each of whom would pledge to purchase the book for the then jaw-dropping price of $5 each. There were to be 10 illustrated full-page (14- × 11-inch) plates per volume, and because the publisher couldn’t print colour images, each lithographed plate had to be hand-painted, which amounted to 5,000 hand-painted plates for a run of 500 books.

On Confederation Day, the 1st of July 1867, Agnes had already recruited more than 400 subscribers, including her second husband-to-be, Colonel Brown Chamberlin, who owned Montreal’s The Gazette newspaper and was later appointed the Queen’s Printer — a particularly fortunate twist of fate.

Having paid her aunt $50 for a much reduced text, Agnes took over the project, drawing the title page and the 10 floral designs on limestone tablets so that colour-ready lithographs could be printed. From July 1867 to December 1868 — with the help of three of her daughters — Agnes painted the 5,000 lithographed plates while Catharine further edited the text and wrote the preface. The finished product went on sale in January 1869, and sold out within six weeks.

Three more editions were printed in Catharine Parr Traill’s lifetime (1869, 1870 and a special limited edition in 1895). Each copy of these historic books is precious, made even more so by the scientifically accurate text, the exquisite hand-painted images and Catharine’s lyrical writing style.

In 1885, the full text of Catharine’s original Hortus siccus was published in Ottawa as Studies of Plant Life in Canada: Gleanings from Forest, Lake and Plain. Still invaluable and still in print, it’s a volume I often refer to when writing about native plants, and once again, her niece (by now Mrs. Agnes Chamberlin) hand-painted all the illustrations from her own lithographs.

Nearing the end of her life, Catharine published Pearls and Pebbles (1894), a collage of her writing from the pioneering 1830s up to and including the many changes she witnessed over the intervening 60 years. Widely fêted as the oldest working author in the British Empire, she died in 1899 at her home in Lakefield, Ontario.

Gardeners interested in the natural history of our home and native land — and its indigenous plant species — can’t do better than to read the works of Catharine Parr Traill, Canada’s first popular chronicler of our native flora and fauna.

Viewing digital versions of these books

These historical books, along with hundreds of original botanical watercolours by Chamberlin, have been digitized by the Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto and the material is freely available for viewing at fisher.library.utoronto.ca/agnes-chamberlin-digital-collection.

Share your comments

We welcome your comments about Canada’s horticultural history.

How timely … recently looking at Catharine Parr Traill’s “Canadian Wild Flowers” (reprint by Algrove Publishing Ltd., 2003). I was thinking I’d love to frame some of the illustrations but don’t to cut from the book. Delighted to learn prints are available through your link. Thank you.

Thank you for the link and information. It’s very timely for Canada’s 150th celebrations and awesome to see the digitization of important botanical art collections.

Wow, what a great incursion in a part of canadian botanical history I didn’t know. Thanks!