Cool days are here, and it’s time to address the more arduous tasks that we avoided in warmer months: soil renovation. Now that we know full-scale tilling and turning over of soil disturbs the delicate microbial systems at work beneath our feet (no more double digging!), we can be more selective about where to make improvements. My strategy is to improve the drainage and oxygen content in the soil surrounding perennial plants, and anywhere I’m counting on plants to produce sustained bursts of bloom through the season.

Perennials starved for oxygen can’t make lots of flowers. Plants take up oxygen (and nitrogen in gaseous form) through their roots, and a healthy supply is essential for flower production. Dense or compacted soil has few pores, or air spaces, for water to drain away and to allow oxygen to penetrate the root zone.

How to do your own soil renovation

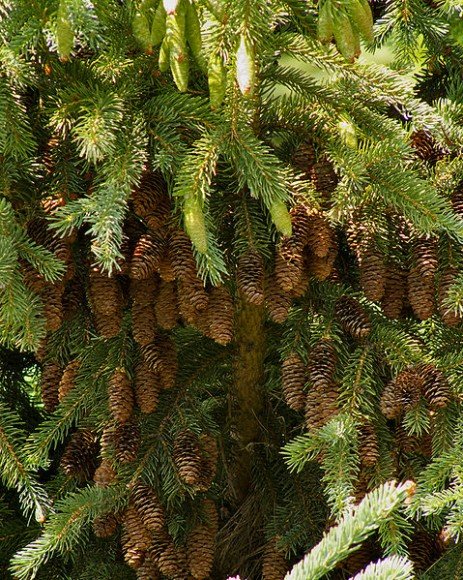

I dig in generous amounts of leaves around perennials when I divide or move them, and also the cones from a white spruce tree (Picea glauca, Zone 3) brought down from a neighbour’s cottage and planted in my garden six decades before I lived here—so it’s not a baby! The small cones that fall on the lawn are simply trodden in, and I collect a basket from under the tree to use as a soil amendment. Their bulky form holds oxygen in the soil, and they’re just the right size for roots to grow around in planting holes. Yes, a gardener’s eccentricity, but I wouldn’t be without them. You might find a white cedar in a city park, on a university campus or at your cottage, and now is a good time to look for cones under it. I also have a large Norway spruce (Picea abies, Zone 4), which produces bushels of wonderful needles I also use in planting holes.

Another soil amendment I rely on is rock in various sizes and forms. Using rock materials as amendments improves the porosity of clay-based soil. Of course, rocks come in many mineral compositions and sizes. The one rock material absolutely not to use in soil is limestone screenings, which are used as foundation for stone or brick walkways and patios. Limestone screenings are chalky-white crushed pieces of almost pure lime, and highly calciferous (alkaline)—plant roots shrivel up in contact with them. Fortunately, they are manufactured and not something you’d find lying about the garden, so you’ll easily avoid them.

I always have a bag or bucket of simple crushed stone grit, or quarter-inch gravel, or half-inch pea gravel that I mix into planting holes to improve the movement of water and oxygen around plant roots. If a perennial is doing poorly, but shows no signs of disease, I’ll lift it and renovate the hole with whatever rock material is on hand, then settle the plant back in. It’s often difficult to identify the mixed mineral components of these materials, but my general rule is never use rock that appears too white (that lime issue again). Dark or dull grey (sometimes splashed through with semi-translucent quartz, or sparkly with mica) is always a good sign as it indicates the presence of granite, an acidic igneous rock that helps balance the pH of our alkaline soils in southern Ontario.

Finding these materials isn’t always easy, and construction-supply yards and stone quarries often require a minimum purchase of several cubic yards. Sometimes they will admire your interest and allow you to fill your bucket for a small cost (or no cost at all). The easiest rock material to acquire is coarse builders’ sand, sold at home improvement stores. The particles in play sand or horticultural sand are too fine and small, and will make soil dense, quite the opposite of creating pore spaces. Roll sand between your hands to test the particle size—play or horticultural sand will be soft and smooth, and you won’t feel individual grains. But coarse builders’ sand has larger particles, and it will be sharp, with individual grains you can feel. No, I don’t have rocks in my head—they’re in my garden soil!

Defeating the columbine leaf miner

Cleaning up the garden gives me a chance to remember how much pleasure has come from individual plants—in this case, dwarf Biedermeier columbines (Aquilegia Biedermeier Group, Zone 4), sometimes known as the nosegay columbine because of its flower-packed stems, just ready to be cut for a small bouquet. Let me say they aren’t really so dwarf—described as 12 inches (30 cm) tall, but more like 18 inches (45 cm) in flower. Columbines are usually short-lived perennials, disappearing after a few seasons. But my Biedermeiers have hung on for five years, and produced a few seedlings with clear and attractive colours. I think it was Patrick Lima who wrote about their resistance to columbine leaf miner, a pest I have herds of here on the ranch! You’re probably familiar with the circuitous white tracks they weave through leaf tissues, eventually sapping the plant of energy and causing wilt. But the Biedermeiers are not to their taste and the miners leave them untouched. The strain has benefited from a bit of the hybridist’s art, and their flowers are outward facing and fully visible.

Still blooming: yellow fumitory

What would I do without yellow fumitory (Corydalis lutea, Zone 4)? It seems to have the genius of finding a perfect place for itself, filling vacant dusty corners and draping sprays of bright yellow flowers over rocks and between the bare ankles of shrubs—but never anyplace where I would want it removed. Does this plant read my mind? In mid-October yellow fumitory is as bright and full as it was in July. It spreads by seed, and acquiring just a few pots will insure you have it for all time. If it should pop up inappropriately, a gentle sigh of dissatisfaction will easily remove it.

Thanks for stopping by at Garden Making—hope to see you next week.

To Dianna, Oct. 23

Dianna,

You don't mention which species of jasmine you have, but all of them are frost tender and can't survive outdoors in a northern winter. To save the plant, it must be brought indoors.

Jasmine usually blooms in January when grown indoors, and it blooms on only new growth. If it's very long and tall, you can cut it back by about half and fertilize it once to see if you can trigger new growth. But if it's a manageable size, there's no need to prune it; fertilize the jasmine and it may produce a bit of new growth this autumn. Indoors (during November and December) it will need a bright location during the day and complete darkness at night, as well as cool night temperature between 40F to 50F (5C to 10C) to set flower buds. The soil should be kept slightly dry while you're trying to induce flowering. If you don't get any flowers in January, cut the plant back by half in late winter, fertilize it, and take it out again in mid spring when all danger of night frost is past. Then you can expect flowers sometime in late spring or early summer. Good luck!

It's a lot of effort, but perhaps will be an interesting experiment. And of course you can always purchase another jasmine plant next spring.

I have a jasmine that's about 6ft. tall in a huge whisky barrel tub. It has done very nicely all summer, BUT, how do I keep it over winter? Our back yard has three levels, the back of the house walks out to the lower level we have a 18 ft canopy over our patio and then straight out from the patio there is a 4ft retaning wall. There is a lot of wind that tunnels thru the back yard. We have put up a commercial tarp around the one end and half way across the front so we have some pertiction from the wind. Would the jasmine be safe if I put it in the corner where there would be more protection during the winter? Please tell let me know how to care for it over winter. I don't want to lose it.

To Denyse, Oct. 23

Denyse,

Have hope! If you're dealing with only one tree and not a small orchard, there is certainly a possibility of improving your crop quality. It sounds like you're alrady familiar with organic growing practices; but if you'd like to refresh your thoughts, you could read a good overview of organic fruit tree growing in The Harrowsmith Book of Fruit Trees, by Jennifer Bennett (1991, Camden House Publishing). This book is likely out of print, but a library should have a copy.

With respect to apple maggot in particular (and your wormy apples), there is a new organic pesticide material call Surround WP, developed by the USDA Agricultural Research Service in cooperation with Englehard Corporation of Iselin, New Jersey. It's a kaolin clay-based powder which can be sprayed on bark, fruit and foliage to confuse the egg laying moths. There are good reports about this product, and it has been highly effective against all the major apple insect pests. There is also evidence that Surround WP increases photosynthesis by keeping the tree cooler in the hottest parts of the day. Surround WP is licensed in Canada, and this could really make a difference to your crop. Apple growers in the Anapolis Valley of Nova Scotia are using it; and here is something to read from the Nova Scotia provincial government: http://www.gnb.ca/0174/01740008-e.pdf. You can also do a simple search for Surround WP on google.com or another search engine for other articles to read.

I think you're going to be picking some very nice apples next year!

Can you please give me any info you have on de-bugging my apple tree holistically. I've used sulphur and Mineral Oil for years to NO effect and I really don't want to poison my tree if I don't have to and I sure don't want to cut it down. We get tons of apples but 99% are very wormy. I'm depressed.

To Brenda, Oct. 22

Hi Brenda,

Shrubs of any age move with the least amount of shock when they are out of leaf and their wood is bare. The best time is now, in autumn when they are dropping their leaves and entering dormancy. The next best time is early spring, before their leaf buds break, and the shrubs are beginning to come out of dormancy. If you have no choice but to move a shrub when it is in leaf, be sure to use a liquid transplant solution in the new hole, to ease shock to the root system.

Transplanting Shrubs. I have a Rose of Sharon I want to transplant, when is it best to do it. Also, when is it best to transplant established shrubs.

To Observer, Oct. 19:

Almost every kind of leaf is good for mulch. I like to use small leaves that don't require shredding and won't blow around, like beech and birch, locust and serviceberry. The smaller maples are also ready-to-use, like Tartarian maple, Amur maple, and the Japanese maples. Silver maple leaves are large, but their deeply incised shape curls up and makes them easy to use. It's only the largest maples leaves, like Norway maple, that work best when shredded, or at least broken up with a few passes of the lawn mower after the leaves are entirely dry. You've got good instincts about what to do with leaves — use them!

Now that the leaves are coming off the trees (in this zone anyway), which are the best to rake up for mulch?